Finance

Finance is critical for the implementation of the mitigation and adaptation actions set out in countries’ NDCs. International public financing sources, such as the Green Climate Fund, will not be able to provide the large-scale investment needed on their own; hence, financing sources such as the private sector and domestic fiscal budgets will be required. Strengthening finance from domestic and external sources will also support the implementation of the SDGs, in particular those on ending poverty (SDG 1), economic growth (SDG 8) and reducing inequalities (SDG 10). 76 Similarly, many of the INDCs submitted included conditions for their full implementation, such as additional or enhanced international support in the form of finance, technology transfer, technical assistance and capacity-building. Improving access to public and private financing sources is therefore a high priority.

Many countries are considering the development of a country climate investment plan. These set out the programme of investments required to implement their NDC, and include a strategy for meeting those financing needs (noting that most NDCs do not include sufficient detail to represent investment strategies). In order to access finance, countries need clear project concepts as a minimum, and financing propositions need to be developed. Furthermore, specific institutional capacities may need to be demonstrated, and the enabling environment for policy implementation and private sector engagement may need to be enhanced (being mindful to address not only financial barriers but also relevant technical and institutional barriers).

The specific funding criteria and access requirements differ between financing sources, but there are common underlying principles that countries can address to increase financial flows and improve their readiness for financing. Many climate funds have specific requirements (e.g. relating to gender, fiduciary criteria and/or environmental and social safeguards), as well as seeking demonstrated synergies between climate projects and national development priorities.

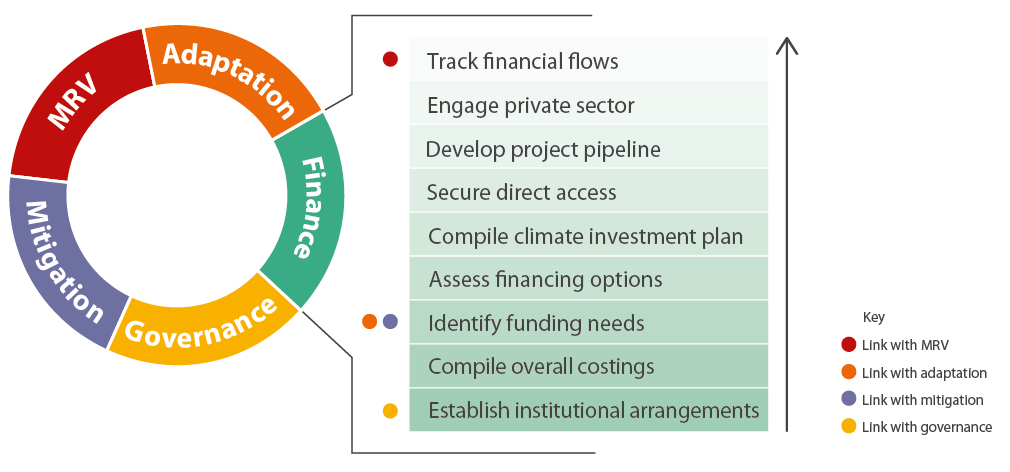

When reviewing this module, countries may find it useful to refer to the mitigation and adaptation modules to consider the financing needs of individual mitigation and adaptation actions; the MRV module with regards to tracking climate finance flows; and the governance module with regards to the institutional structures and processes needed for climate finance.

Box 6. Finance and the Paris Agreement

“Developed country Parties shall provide financial resources to assist developing country Parties with respect to both mitigation and adaptation in continuation of their existing obligations under the Convention.” – Article 9.1

Finance is primarily covered by Article 9 of the Paris Agreement, which re-establishes the precedent that developed countries should take the lead for mobilising finance (Article 9.3). Details on the finance pledged and provided will be biennially communicated by developed countries (Articles 9.5 and 9.7). Developing countries can also contribute to finance but this obligation is voluntary (Article 9.2). The provision of financial resources should aim to achieve a balance between adaptation and mitigation (Article 9.4). Note that Article 6 of the Paris Agreement covers the use of market mechanisms, which may also provide a source of finance for mitigation and adaptation actions.

Key activity 1: Review current climate finance landscape

1a. Review the NDC

- Identify any international support requirements that may have been specified in the NDC, including financial, capacity-building, technology transfer or other types of international support.

1b. Review the current status of climate finance strategies

- Climate finance strategies could include: any existing climate investment plans or policies that may be in place, whether at the national, subnational or sectoral level; work programmes established with any specific bilateral or multilateral funders; Clean Development Mechanism 77 project pipelines; and Nationally Appropriate Mitigation Action (NAMA) project pipelines or work programmes.

Key activity 2: Establish institutional arrangements for the oversight and coordination of climate finance activities

See activity 3 in the governance module for additional content regarding institutional arrangements.

2a. Identify and delineate key roles on climate finance within the country

- Consider internal government focal points with important bilateral and multilateral funders for adaptation and mitigation projects.

- Consider establishing a cross-ministerial working group to enhance coordination on climate finance issues between these parties.

2b. Identify a team within government to lead on national climate finance coordination

- This could be within the ministries of finance or environment, planning commissions or the prime minister’s office. It should ideally be a gender-balanced team and have the mandate to:

- strategically plan and coordinate the access, mobilisation, disbursement and tracking of climate finance across the country

- establish and maintain communication with government focal points and with bilateral and multilateral funders

- ensure coordinated engagement with funders via these government focal points

- disseminate information to country stakeholders regarding funding criteria and the operational requirements and procedures of major funders.

2c. Mainstream climate change into national budgeting processes

- This will ensure NDC implementation priorities are reflected in budgets, helping existing policies, programmes and project pipelines to be ‘green’.

- This can potentially increase domestic, as well as international, fiscal support for climate change initiatives.

- See the case study on Ethiopia’s Climate Resilient Green Economy for an example of how mainstreaming could be implemented in practice.

Key activity 3: Compile an overall costing for the NDC

3a. Undertake a desk review to identify and cost the main sub-actions within each mitigation and adaptation action

- Costing each action involves identifying the cost for sub-actions, including upfront capital costs (e.g. infrastructure), ongoing maintenance costs, capacity-building or training, and the human resources needed to implement the action.

- A desk review could include an assessment of similar actions previously completed within the country, at national and/or subnational levels, as well as reviewing how similar countries may have costed such actions.

- Note that costs for some actions may change over time; it may be necessary to reconsider cost estimates as new information comes to light. For example, costs may decrease over time due to falling technology costs or barriers being removed by relevant policies.

3b. Check these desk-based estimates with relevant national experts and stakeholders

- Checking the results of the desk-based review with relevant experts can provide additional confidence that the costings are roughly correct and that no important elements have been overlooked.

- Relevant national experts could include government ministries, departments and agencies that are expected to lead the implementation of the actions, have been involved in implementing similar actions, or have experience in costing similar actions (e.g. planning or finance departments). They could also be private sector investors or academics.

Key activity 4: Identify funding gaps and needs

See activity 6 in the mitigation module and activity 4 in adaptation module for additional information on financing actions under these areas.

4a. Scope and prioritise the actions to be undertaken during NDC implementation

- See the mitigation and adaptation modules for more detail on scoping and prioritising the actions; in summary, this will likely involve:

- identifying the range of actions that could be undertaken to implement the mitigation and adaptation components of the NDC

- prioritising these actions, in close consultation with key country stakeholders

- undertaking a broad barriers analysis, and other analyses, to assess the enabling environment for each action (e.g. domestic policy support frameworks, institutional barriers) and understand the mix of financial and non-financial measures required to successfully implement each action.

4b. Assess the funding status of each priority NDC action

- Identify existing and projected domestic budgetary support for each priority NDC action, for example through the development of Climate Public Expenditure and Institutional Reviews 78 or other frameworks.

- Consider available domestic budgetary support, as well as any expected bilateral and/or multilateral support and private sector finance.

- Identify which actions and sub-actions have yet to be fully funded.

4c. Identify the level and type of support needed to address each funding gap

- Assess the amount and type of support required to close each funding gap (e.g. capacity-building, technical assistance, finance) and the likely type of funding source (e.g. government, bilateral and multilateral funders and private sector).

Key activity 5: Assess public and private financing options

5a. Assess the potential for further domestic fiscal support for each action

- Review existing development policies, programmes and infrastructure project pipelines to assess the potential for ‘greening’ these activities, for example extending or amending these to include NDC priorities, and screening the climate risks or mitigation potential associated with these projects.

- Identify opportunities to mainstream climate change priorities into the national budgetary and infrastructure planning process. This can indirectly increase domestic and international fiscal support for climate change initiatives. See the governance module for more details regarding integrating NDC implementation across government.

- Additional engagement with key departments may be required, including planning, finance and sectors involved with NDC implementation, at both the national and subnational levels.

- Consider what information on the co-benefits of climate action might be useful to these departments, to obtain buy-in and support.

5b. Assess the eligibility of each action against bilateral and multilateral funding sources

- Consider the country’s history of accessing funds from bilateral and multilateral sources to identify potential funders with whom the country already has a relationship. These could potentially be approached in the short-to-medium term regarding financing for priority NDC activities.

- Identify any new sources of multilateral and bilateral finance that could potentially support the actions.

- Assess the eligibility of each action against the funding criteria for existing and potential new bilateral and multilateral funding sources.

- Identify the best method for the country to access each funding source, for example direct access (this is relevant for a limited number of funds; see activity 7 within this module), indirect access, or NAMA development.

5c. Assess options for private sector investment for each action

- Assess the suitability and potential attractiveness of each action to the private sector. This can be done by determining if the action is likely to generate a predictable future revenue stream that can cover the costs and generate profit (e.g. electricity sales to consumers where there is large unmet energy demand), or if the government may consider directly paying private sector investors (e.g. a public–private partnerships where assets are built and the government pays investors for delivering services).

- If the annual net cash flows will be insufficient, a range of financial and non-financial interventions can be considered (see activity 8 within this module).

- If investors are hesitant to make significant investments in climate-related projects, consider whether smaller, more manageable projects can be financed initially (e.g. demonstration or pilot projects), thereby improving the financial track record for the sector or technology, which should increase market interest.

Key activity 6: Develop a country climate investment plan

- A country climate investment plan sets out the programme of investments required to implement each priority action in the NDC, as well as a strategy for meeting those financing needs. Examples of sector-specific climate investment plans can be found on the Climate Investment Funds website. 79

- Developing the country investment plan will involve consolidating the analysis undertaken across activities 3, 4 and 5 within this module, and making decisions regarding which funding options are most appropriate for each action.

- When developing the climate investment plan, it may be useful to review how peer countries deliver and finance similar projects and what lessons can be learned.

- The country climate investment plan should build on and strengthen any existing climate investment plans in place, as well as drawing on Clean Development Mechanism or NAMA project pipelines and country programmes that have been developed for specific bilateral or multilateral funders.

Key activity 7: Secure direct access to international climate funds for national and subnational institutions

- A limited number of international funds allow direct access, including the Green Climate Fund, the Adaptation Fund, the Global Environment Fund and the European Commission Directorate-General for International Cooperation and Development.

- Direct access involves national or subnational institutions directly receiving finance from funding sources and disbursing them to relevant projects, i.e. without an international agency managing and overseeing the funds as an intermediary.

- Each fund has different accreditation requirements for institutions seeking direct access, including demonstrating capacities such as financial and administrative management, monitoring and evaluation (M&E), project management, gender mainstreaming and equity, and environmental and social management.

- Countries that are interested in direct access may find it useful to initially screen a selection of national and subnational institutions against the accreditation requirements for the relevant fund or funds, to identify potential eligible institutions and the resources required to fully meet the accreditation requirements.

- For countries with institutions that are already accredited (depending on the funding source, these may be referred to as ‘accredited entities, ‘implementing entities’ or similar), the next step may be to develop a project pipeline and put forward funding proposals so that finance can be accessed (see activity 8 within this module).

- Note that the institutions that will be seeking to access financing sources may not necessarily be the same as those leading the implementation of the actions.

Key activity 8: Develop a project pipeline and financing propositions that can be put forward to different financing sources

8a. Build technical and relational capacities within government ministries to develop a project pipeline

- Capacities that can support the development of a project pipeline include:

- the ability to undertake financial and technology needs assessments across the country’s priority sectors, to assess where efforts need to be focused and ensure projects are robust

- technical understanding of available technologies to ensure the most suitable and effective technology is being used

- coordination with relevant ministries to develop joint project proposals and navigate ministerial priorities

- financial modelling and cost–benefit analysis expertise to determine the financial feasibility of the proposed projects and ensure projects stay within the country’s budget

- writing skills to develop business cases and project concept notes, to ensure the most effective outcomes for implemented projects

- the capability to design and select climate change projects and programmes.

- Any climate change-related capacity-building could potentially include the integration of SDG principles into project concepts, especially gender equity.

- Implementing the NDC will require a strong pipeline of climate change projects, as well as integrating climate-related activities into existing and proposed infrastructure programmes. This is likely to involve initiatives led not only by a country’s ministry of environment, but also ministries of planning, transport, energy and others. To support the integration of climate-related activities into infrastructure projects and programmes, it may be helpful to build capacity across all government departments involved in NDC implementation.

- In addition, there may be non-government stakeholders who have key roles to play in the design and selection of climate change projects. It may be useful to include them in any capacity-building programmes.

8b. Develop funding proposals that can be shared with bilateral and multilateral funders

- Many bilateral and multilateral financing sources allow for the submission of project concept notes, so that initial feedback can be received on the eligibility and viability of the project, before preparing a full funding proposal.

- Requirements for full funding proposals will vary between funders, with typical requirements including information about financing requirements (e.g. co-financing to be provided by the country), as well as a detailed description of project activities and the anticipated results.

- When preparing funding proposals, be mindful of any concept note or proposal templates provided by the funder, as well as the eligibility criteria.

- Some funders may provide support for the development of project concepts and proposals.

- It may be useful to meet with the funder to receive early feedback on project ideas, and how they fit with the funder’s selection criteria.

8c. Develop funding proposals that can be shared with potential private sector financing sources

- It may be useful to meet private sector investors to receive early feedback on project ideas, for example through roundtable discussions and consultations (see activity 9 within this module for further information on private sector engagement).

- The private sector will typically seek funding proposals that address the following concerns:

- Is the technical solution well thought through?

- Does the technology have a track record?

- Are there the skills available within or outside the country to develop the project?

- What remedies are available if projects are poorly built or operating costs are higher than expected (e.g. enforceable performance bonds from construction companies)?

- Where will revenues to pay financiers come from (e.g. sales to customers, government support, concessions)?

- What reassurance can be given that the revenues will be achieved (e.g. additional government support, government-backed guarantees and credit ratings, minimum price agreements and realistic demand forecasts)?

Key activity 9: Increase private sector engagement and overcome barriers to investment

9a. Assess and enhance the domestic investment environment

- Identify the barriers to private sector investment across relevant priority actions for NDC implementation. These can include perceived or actual risks (e.g. credit risks, policy or political risks, technology risks), the scale of investment opportunity available (e.g. transaction costs are too high in relation to the size of the opportunity), or returns are too low (e.g. due to interest rates and taxes).

- Identify the range of financial and non-financial interventions needed to address barriers for private sector investment across relevant priority actions for NDC implementation.

- Financial interventions include: risk-mitigation instruments (e.g. policy risk insurance, government or donor-backed partial guarantees); concessionary loans (e.g. to improve the financial viability of projects); grants (e.g. to improve financial viability of projects or climate-risk assessments and energy-efficiency audits); aggregation instruments (e.g. to increase the scale of investment opportunity); tax breaks (e.g. for low-carbon or climate-resilient technologies); feed-in tariffs (e.g. to incentivise renewable energy); and public–private partnerships.

- Non-financial interventions include: strengthening the rule of law (e.g. so that investors can seek compensation if energy companies do not honour offtake agreements); developing ‘matchmaking’ services (e.g. between project developers and financiers); capacity-building for the financial sector (e.g. to address perceived risks associated with low-carbon or climate-resilient technologies); and knowledge transfer (e.g. writing step-by-step guides for developing projects, preparing legal templates for power purchase agreements, rental agreements and loan agreements).

- Develop public–private financing structures and launch pilot projects to showcase viable business models and attract further climate investment.

- Review the approaches used by peer countries for public–private financing and consider whether they could be applicable.

9b. Strengthen the capacity of relevant departments to identify and develop financially viable opportunities for the private sector

- Capacities that can support government officials to identify and develop financially viable opportunities for the private sector include:

- understanding how projects similar to the actions being considered are normally financed in the country, to help build financial models for individual projects; this includes understanding: what loan sizes are common in the country? How long do most loans last for? In which currency are most loans? What interest rates are normally charged? Is there a bond market or an active equity market? Do banks from outside a country lend to a project?

- knowledge of financial and investment terminology (e.g. payback periods, internal rates of return, equity returns, pre-tax and pre-finance project returns)

- understanding of the constraints and requirements of investors (e.g. banks typically need to see sufficient net cash flows to comfortably pay loans)

- knowledge of the range of financial and non-financial mechanisms available to increase the financial viability of projects for the private sector, and to reduce risks (e.g. the risk of cost overruns, revenue streams being lower than anticipated), as well as different ways to call for private sector involvement in projects (e.g. funding competitions, bidding for projects)

- skills and experience in conducting commercial negotiations with the private sector.

9c. Increase private sector engagement in national climate policies, strategies, coordinating committees and national financing bodies

- Promote greater public–private dialogue on climate finance through regular forums and institutions. These can include sectoral associations, investor platforms and public consultations.

- Increasing public–private dialogue can lead to increased understanding of climate change opportunities within the private sector, as well as an increased appreciation of investment barriers and how these can be addressed.

- Involve the private sector in the design and implementation of national climate change policies and projects, to better understand investment barriers and jointly explore opportunities.

Key activity 10: Design and implement a climate finance MRV system

See the MRV module for further details on designing and implementing a climate finance MRV system.

10a. Identify climate-related spending across all relevant finance flows

- Building on any finance MRV systems that are in place (e.g. for Biennial Update Reports), develop standard methodologies and key performance indicators for a climate finance MRV system, including agreeing a definition – with all relevant stakeholders – of what constitutes climate change-related activities.

- Identify all the relevant departments and institutions that are likely to receive climate finance, and put in place data-sharing agreements (e.g. memoranda of understanding) between relevant departments and institutions, and the climate finance tracking team.

10b. Track and report climate-related spending across all relevant finance flows

- Introduce regular reporting on climate activities for government ministries and implementing entities, using standard key performance indicators to ensure data comparability.

- Develop a central tracking system that allows users to input data using standard templates.

- Process and analyse data on a regular basis, delivering findings in a report that can be used to guide the strategic thinking of the team leading national climate finance coordination.

10c. Expand and improve the MRV of climate finance

- Refine the MRV system based on the lessons learned, and extend the scope of funding tracked to all donors and all relevant institutions over a number of years.

- If Biennial Update Reports have presented data on international climate finance received, assess and revise definitions to ensure they match the NDC targets and ensure the list of institutions involved is complete.

- Assess gaps and close them, step by step, over a longer time frame.

Learning from others

Case study 15. Ethiopia: improved access to finance through the development of national central funds

The Government of Ethiopia’s Climate Resilient Green Economy Facility is the primary mechanism to mobilise, access and combine domestic and international, and public and private, sources of finance to support the institutional building and implementation of the country’s Climate Resilient Green Economy Strategy. The Facility became operational in 2012 and is expected to run until 2030. It is housed within the Ministry of Finance and Economic Cooperation and is governed by the Climate Resilient Green Economy Ministerial Steering Committee, chaired by the Prime Minister’s Office, which determines the overarching priorities.

This set-up has several benefits.

- Flexible, coordinated and predictable funding. As a central fund, the Facility provides funding through a variety of financing instruments: loans, co-financing, results-based payments and grants for actions and projects that are in line with the national strategy and development goals. Funding is provided to implementing entities at federal and regional levels to undertake projects in line with the Climate Resilient Green Economy Strategy.

- Greater coordination between climate change activities. It provides a single point where stakeholders can come together and make decisions about climate change issues, increasing cooperation, efficiency and effectiveness.

- Competent monitoring, tracking and reporting of finance to donors. Each quarter, the government publically reports the total funds received and disbursed, including expenses. Annual audited financial statements are also published. The Facility has detailed operational manuals in place, which can be used to demonstrate to donors that fiduciary standards are in place to ensure finance is being used for the intended purposes.

- Enhanced private sector engagement. The Facility gives confidence in government actions, which in turn ensures that private sector concerns and market barriers can be clearly acknowledged in design and implementation plans. 80

Case study 16. India: using the Clean Development Mechanism to finance gender-responsive mitigation

The Indian Bagepalli Clean Development Mechanism Biogas Program was registered in 2005 as the world’s first pro-poor Clean Development Mechanism project. 81 It introduced 5,500 biogas units that convert cow dung into cooking fuel and provided clean stoves for poor households. This is a good example of a climate financing mechanism that has delivered mitigation, adaptation and development co-benefits, and has been conducted in a gender-responsive way.

The project has improved the overall quality of life and social well-being of families, in particular women and children. It has reduced the collection of fuel wood, increased access to energy and made cooking easier. This has freed up time for women to engage in income-generating and other productive activities. It has also reduced indoor air pollution, improving families’ health. Communities involved in the programme, especially women, have benefitted from the income generated by selling emission credits. 82

Case study 17. Uganda: mobilising private sector development of small-scale renewables using a feed-in tariff

The Ugandan national grid faces a looming power-supply shortage, which threatens economic growth. Currently, there are significant barriers to the introduction of small-scale renewables due to a lack of proper incentives or a consistent, transparent legal and policy framework.

The Global Energy Transfer Feed-in-Tariff (GET FiT), launched in May 2013, aims to encourage private investment in renewable energy projects in Uganda to improve economic growth, reduce poverty and mitigate against climate change. Specifically, it aims to fast-track 20 small-scale renewables projects, totalling 170 megawatts and 830 gigawatt hours per year. It was developed by the Government of Uganda, Uganda’s Electricity Regulatory Authority and the German development bank KfW, with support from other national governments and funds and the World Bank. By the end of 2015, there were 17 projects under construction or delivery across Uganda, including one biomass project, two solar photovoltaic projects and multiple hydropower projects. 83 The 17 projects have a combined capacity of 157 megawatts.

The programme uses several approaches. The GET FiT Premium Payment Mechanism is the main support lever. This is a results-based premium payment designed to top up Uganda’s own renewable energy feed-in tariff. These top-up payments are made to renewable energy projects to deliver energy to the national grid over 20 years. Support is front-loaded so that funds are paid out over the first five years of operation, during early debt-repayment periods, thereby facilitating commercial lending.

The scheme also solves technical, regulatory and legal problems. Support has been provided to review, update and standardise legal documents required for project delivery in order to reduce transaction costs and times. Key stakeholders, including developers, their banks and lawyers, were involved in a consultative process to ensure broad acceptance of the revised documents.

The GET FiT M&E framework monitors the programme’s outputs, outcomes and impacts. Quantitative indicators are collected from project developers and important stakeholders, and biannual performance reviews are conducted by an independent consultant. These aim to critically and independently assess whether GET FiT is meeting its targets and objectives.

Case study 18. Bangladesh: the Solar Homes System Program

The Solar Homes System Program is one of the largest and the fastest-growing off-grid renewable energy programmes in the world. It aims to provide clean energy to off-grid areas in Bangladesh, and forms part of the government’s vision of ensuring ‘Access to Electricity for All’ by 2021. It has been driven by the Infrastructure Development Company Limited (IDCOL), a state-owned infrastructure-financing bank, with support from development partners such as the Asian Development Bank. Since its launch in 2003 it has provided solar energy to 3.5 million households in off-grid areas. This has enabled 24-hour energy access and reduced the use of kerosene lamps, which produce emissions that damage health.

A strong partnership: Key to the success of the programme has been the collaboration between IDCOL and its network of over 50 grassroots partner organisations. These partner organisations implement the programme by selling, installing and maintaining the solar systems. IDCOL also works with a number of development organisations, including the World Bank, the UK Department for International Development and the Global Environment Fund, among others. These have provided financial and technical support for the implementation and expansion of the programme.

Innovative financing schemes: IDCOL screens and selects partner organisations, and then provides them with refinancing and grant schemes. It has proved to be a good way to make private domestic household money available through public initiatives for solar energy.

Positive welfare impacts: The impact of the programme on education and home-based work (mostly of women) has been significant. The lighting system extends waking and working hours, and allows more time for productive household activities, reading and studying, as well as social interactions. Lighting also provides greater security, which has had a positive impact on women in particular.

Case study 19. India: mobilising finance to implement the NDC through green bonds

India’s NDC has an ambitious target of adding 175 gigawatts of renewable energy capacity by 2022. It is estimated that this will require funding of US$200 bn and will therefore require the involvement of international capital markets, via innovative instruments like green bonds.

In its NDC, India included the introduction of tax-free infrastructure bonds worth INR 50 bn (US$794 mn) for the funding of renewable energy projects during the financial year 2015/16. It also focused more on technical support and broadening investor opportunities, including allowing 100% foreign ownership of renewable projects. By doing so, the Government of India is helping to make the business case for NDCs. And in January 2016, the Securities Exchange Board of India rolled out a concept paper defining the guidelines for issuing and listing green bonds to further facilitate their uptake in India.

Growth in Indian green bonds: The YES BANK, India’s fourth-largest private sector bank, successfully issued the country’s first ever green infrastructure bonds in 2015. The bank made a commitment to support clean energy projects to produce 5,000 megawatts by 2020. After this, in March 2015, another leading banking institution, the Exim Bank of India, issued a five-year US$500 mn green bond, which is India’s first dollar-denominated green bond. The Exim Bank will initially use the net proceeds to fund eligible green projects in other countries, including Bangladesh and Sri Lanka.

In June 2016, India’s Axis Bank launched the country’s first internationally listed and certified green bond and raised US$500 mn to finance climate change projects around the world. The bond, certified by the Climate Bonds Standards Board, has been listed on the London Stock Exchange. 84

- 76 See Appendix 2 in the Quick-Start Guide for more details.

- 77 UNFCCC (no date) ‘Clean Development Mechanism – CDM’. Bonn: United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. (https://cdm.unfccc.int)

- 78 UNDP (2015) Methodological Guidebook: Climate Public Expenditure and Institutional Review (CPEIR). Bangkok: United Nations Development Programme Bangkok Regional Hub. (www.asia-pacific.undp.org/content/rbap/en/home/library/democratic_governance/cpeir-methodological-guidebook.html).

- 79 Climate Investment Funds (no date) ‘Country plans’. Washington, DC: Climate Investment Funds. (www-cif.climateinvestmentfunds.org/country).

- 80 Some information taken from: Global Green Growth Institute (2014) Op. cit.; The REDD Desk (2016) ‘Climate Resilient Green Economy (CGRE) Facility’. Oxford: The REDD Desk. (http://theredddesk.org/countries/actors/climate-resilient-green-economy-crge-facility).

- 81 UNFCCC (2016) ‘Project: 0121 Bagepalli CDM Biogas Programme Crediting Period Renewal Request’. Bonn: United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. (http://cdm.unfccc.int/Projects/DB/DNV-CUK1131002343.1/view).

- 82 Adams, L., Zusman, E., Sorkin, L. and Harms, N. (2014) ‘Making climate finance work for women’. ADB Gender & Climate Finance policy brief. Metro Manila: Asian Development Bank. (www.researchgate.net/publication/276355241_MAKING_CLIMATE_FINANCE_WORK_FOR_WOMEN).

- 83 GET FiT (no date) ‘GET FiT Annual Report 2015’. Kampala: GET FiT Secretariat. (www.getfit-reports.com/2015).

- 84 Bhatt, M. (2016) ‘Feature: India strengthens its credentials for green bond issue’. CDKN blog. London: Climate and Development Knowledge Network. (http://cdkn.org/2016/06/feature-india-strengthens-credentials-green-bond-issue).